The Art of Craftsmanship

People who labor all their lives but have no purpose to direct every thought and impulse toward are wasting their time—even when hard at work. — Marcus Aurelius

I was 15, and I decided it would be good for me if I started to read. I was becoming intimately aware of what was expected of me. It seemed people wanted me to be educated, so I thought I would do that.

I started with When by Daniel Pink. I liked the colors on the front. It’s one of those books that should have been a blog post — simply arguing that the time of the day affects us more than we think it does. But it was a more than just a book — it was a manifestation of an emerging question in my mind.

How do we spend our time?

The Problem — Time

Over the next few years, I learned that time is both something we have far too little and far too much of. Far too little in that so many people die wanting to do more and far too much in that we elect to spend so much of our time in a dazed, half-aware state.

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi sums this up in Flow:

In the roughly one-third of the day that is free of obligations, in their precious “leisure” time, most people in fact seem to use their minds as little as possible. The largest part of free time… is spent in front of the television set.

The paradox of time — that we claim to have so little yet waste so much — is something I wanted to figure out. While I don’t know much about myself and the world, I do know that I don’t want to lie on my deathbed wishing I did more having spent a large portion of my life trying to pass the time by.

But how?

Think of some of the best moments in the past week, month, and year. Here’s some of mine:

Week:

- Learning about graphs in computer science and being in awe of their beauty

Month:

- Working on solving a CS problem while sitting with someone I deeply care about

Year:

- Staring up at the stars in Michigan while one of my close friends and I shared stories

There’s a simple pattern among them: I was completely unaware of time, sometimes I was in awe, and my close friends were often there.

In these moments, I was somewhat egoless, fully immersed in what I was learning about, creating, or simply experiencing. I felt sensitive to the flow of the universe (I have no idea what it means, but it feels right to say).

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi would call this state of being the “flow state.” A state of being we can enter when the conditions are just right. But, I don’t want this to be a sometimes thing, I want this to be a lot of times thing.

I want to wake up and feel in awe of the world. I want to be cultivating my relationships. I want to be working on amazing problems and creating amazing solutions. I want to pursue a vision for myself and the world.

Can I find a solution?

Over the past few months, I’ve had a feeling for what it would look like to live a life in this feeling of flow. I feel it when I take life seriously but curiously. When I am working towards something big but am also not resistant to the unpredictable events of the world.

I’ve picked up rock climbing in the past year, and I am consistently amazed by how one of my close friends climbs. She flows. She moves like water. Every movement isn’t a struggle but a choice. A choice made in congruence with nature.

I want to live my life that way. And I think I know where it begins.

It’s Art

If there were any vocation that people used to describe me, I’d want it to be an artist.

Seth Godin clarifies the line between art and work in his Ted Talk — Stop Stealing Dreams. When we treat what we do as work, we try to find ways to do less. But when we treat it as art, we find ways to do more.

What does it look like to treat your work like art?

The Craftsman

Cal Newport defines the craftsman as honing your respective craft to earn the right to do great work. He offers a sobering reality for doing great work. It doesn’t fall into your lap from the sky — you have to earn it.

But I’m not a big fan of this definition. While I agree that there is value in mastering a craft, I don’t think that great work has to necessarily be earned. Great work is found in the process, not so much the destination.

The artist recognizes this. They treat their work, no matter how insignificant, as a canvas to exert their influence over. They’re intentional in how they place the pieces together. Even with a small degree of autonomy, they can find joy and create value. This is creative expression.

Creativity

At first, you imitate. You write in a pre-determined style. You solve problems that have been solved thousands of times. As an artist, a craftsman, it’s essential to keep in mind why there is value in this: the value is not in solving the problem but in the development of mental models used to solve those problems.

Iteration becomes innovation. Only through doing what has already been done and understanding why it was done can one see that there’s a better way to do it.

Creativity arises from the discovery of first principles. From looking at a construction, breaking it down into the assumptions it relies on and how previous artists interacted with those assumptions. You may discover that those artists interacted with those assumptions in a poor way or maybe you discover, in an Einsteinian way, that those very assumptions are wrong.

To get to this point in which we create, though, we have to be willing to fail. Creativity is inherently vulnerable. The individuals we revere today for their innovation were once ridiculed for their stupidity.

Creativity isn’t about you, though. It’s about sharing what you were fortunate to discover with the world.

The Mountains We Climb

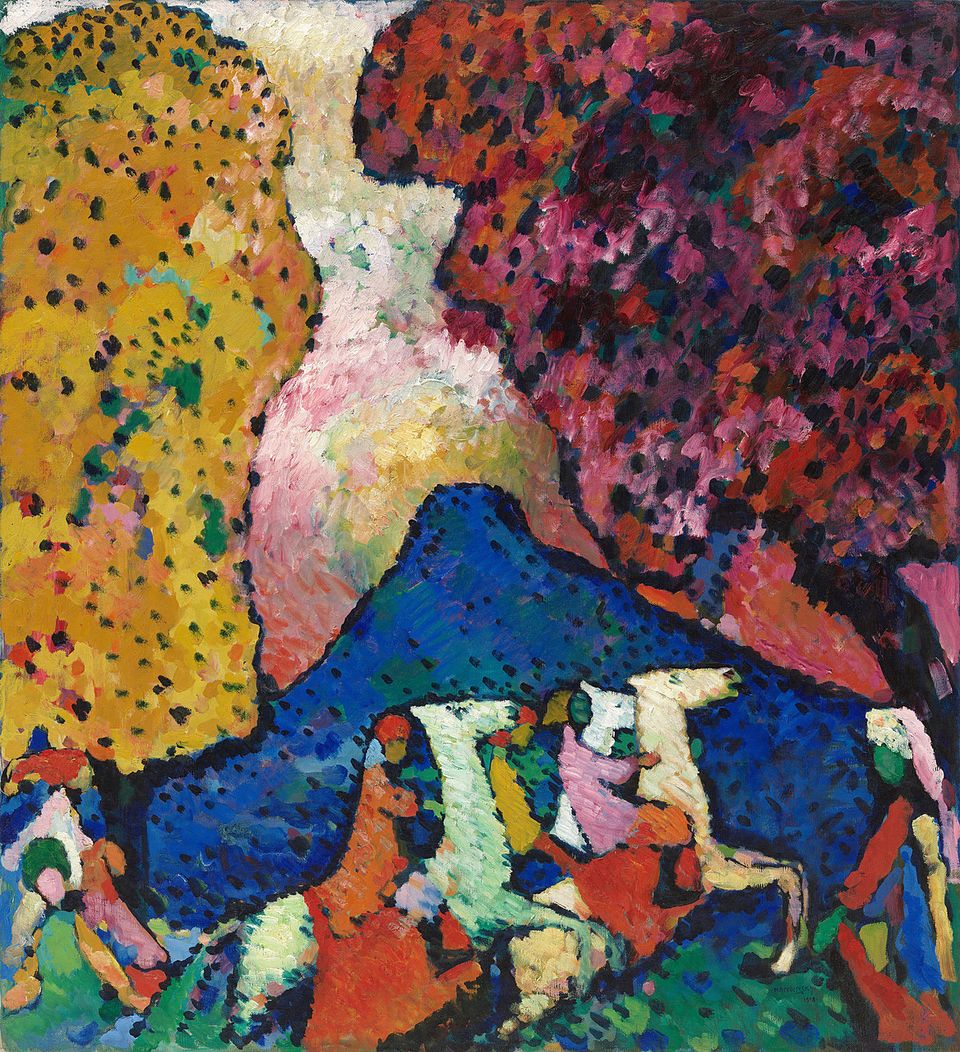

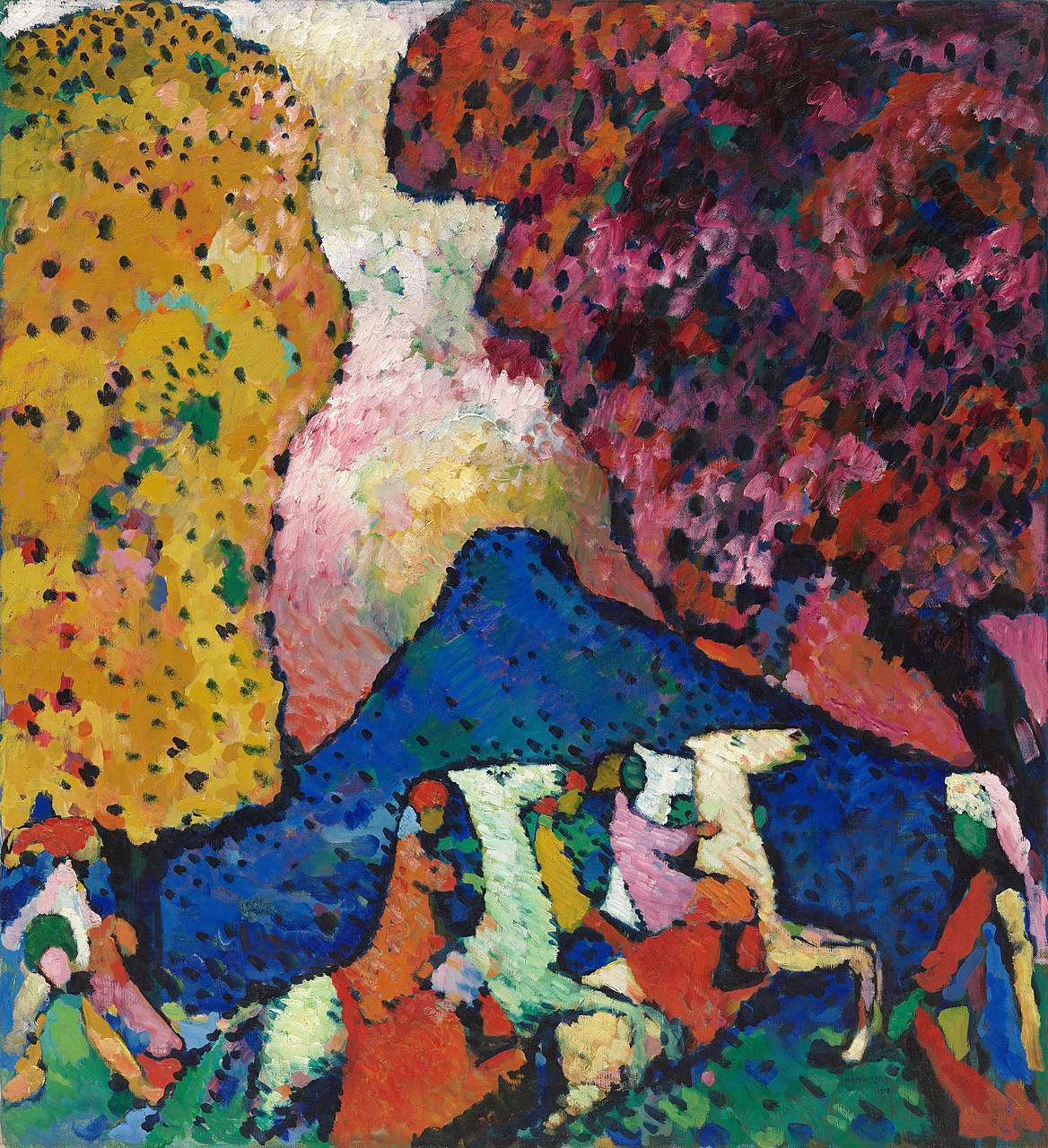

I think Kandinsky’s Der Blaue Berg can help us navigate the journey to becoming an artist. Four unidentified riders set out on the journey to reach the peak of the blue mountain. Who knows where they’re going, but they’re striving.

This is the most important part of human life — aspiration. Striving to reach a better place than where you are while also intimately appreciating and accepting where you are. It is in this space of striving — of bridging the gap between imagination to reality — that we become artists.

The artist always has a mountain to climb. They aren’t ever satisfied. Ray Dalio describes this feeling:

In time, I realized that the satisfaction of success doesn’t come from achieving your goals, but from struggling well.

What can I offer the world?

In discussions with friends about meaning and purpose, I’ve found that many of them are skeptical of the idea that individuals owe the world something.

I’m not going to argue that you owe the world your gifts. But, I am going to argue that making the decision to give the world something may very well lead you to a better life.

Let’s return to Cal’s idea of the craftsman.

Craftsmanship entails a move from a consumer to a creator. From the shaped to the shaper. This transition only emerges from a love of the construction of a field.

However, it’s not simply creating that allows one to be a craftsman — it’s the dedication to creating well. To putting your best foot forward.

A craftsman seeks to create awe. They want their audience to gape, to uncover a hidden truth within themselves, to be enabled to live better lives. It’s a quest — not one that can ever be finished.

I have no philosophical argument for why it’s a worthy quest. In short, I’m choosing to pursue it because I feel my best when I treat my life as art. That’s the mountain I climb, today. And it’s the one I’ll be climbing for a while.